(version anglaise seulement)

Chest Pain: A Practical Approach

Chest pain can be mysterious and deceiving. Regardless of the sensation, it will get your attention. It should. It could be a matter of life and death.

Massage therapy’s scope of practice is limited mostly to musculoskeletal related dysfunction so we will look at some common conditions massage therapists treat and explore some practical methods we use to resolve your pain. Included is a review of the red flags associated with heart attack & angina and how we screen for it in practice.

Caution: Massage therapy does NOT treat heart attack & angina. If you believe you are experiencing a heart attack seek help immediately, tell your medical practitioner if you are with them and call 911. If you have any aspirin on hand take it and chew it.

Functional Anatomical Considerations and Perspective

The chest and back (thorax) is the central structure between the abdomen and neck. Visualize a 3-dimensional barrel-like structure that functions as one unit. As we breathe in and out, the diaphragm moves up and down, expanding and contracting the thorax. See figure 1

Wolff’s and Davis’s laws state that tissue (bone and soft tissue) in the body will remodel itself in accordance to imposed demands (repetitive motions, trauma, posture, lifestyle, exercise, etc.).

Therefore all structures must be considered to reverse and stop dysfunction.

Time and time again in clinic we see individuals come in with one or two complaints, when in reality there are several areas of the body implicated. Our joints need to move unrestricted, our nerves need to freely carry their signals, our muscles need to respond efficiently and our connective tissue must stabilize our movement effectively to enable the chest to move in synchronicity with the rest of the body. Pain will manifest itself when the body fails to meet the demands we place upon it.

Common Conditions

Chest pain represents roughly a third of the cases seen in general practice and hospital setting. In general practice, pain of musculoskeletal origin is the most common diagnosis (1).

Chest pain represents roughly a third of the cases seen in general practice and hospital setting. In general practice, pain of musculoskeletal origin is the most common diagnosis (1).

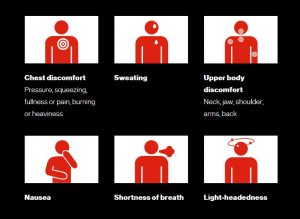

Angina & Heart Attack: Angina occurs when a vascular obstruction or narrowing of any kind blocks blood supply to the heart muscle (7). Heart attacks occur when the blood vessel blockage is more severe or complete. See Table 1 an overview of the warning signs associated with heart attack & angina.

Costochondritis: This condition is characterized by tenderness local to articulations of the ribs, rib cartilage and where the ribs meet the sternum with no associated swelling. Pain may present superficially to deep and can refer into the abdomen (1, 3).

Intercostal Neuralgia: This condition involves compression or irritation of the nerves of the rib musculature. Nerve pain and altered sensation is experienced locally and radiates throughout the rib area. This condition typically arises following blunt force trauma, disease, muscle tension or after resting in a compromising position for a pro-longed time such as sleeping awkwardly. One virus in particular that causes intercostal neuralgia is varicella-zoster. Commonly known as the shingles virus in adults. This infection causes a rash. In severe cases this virus can attack the intercostal nerves, thus resulting in the nerve pain described above (1, 3).

Sternalis Syndrome: This syndrome is characterized by tenderness present in the sternalis muscle and its facial connections to surrounding structures. This muscle is rare and not commonly found amongst everyone, however is still important to be considered as a differential cause (9). Like most muscle strains, it will have tender points that show a positive jump sign (muscle twitch) when palpated. Pain is felt deeply in the middle of the chest and can radiate in either direction into the chest muscles and arms but is not aggravated by upper body movement (8). A severe enough acute presentation of this condition can easily give the impression of a heart attack (1).

Costovertebral Dysfunction: This condition is distinguished by abnormal movement of the joints where the ribs articulate with the spine. Contributing factors include, poor posture, trauma and abnormal changes to the joint itself. Range-of-motion is affected, pain is local and often radiates across the middle of the back occasionally to-wards the chest (similar to intercostal neuralgia) (1).

Chest Strain: A strain is damage to muscles, tendons and connective tissue with contractile properties such as fascia. A sprain is almost exclusively used to describe ligament damage. Acute symptoms can include decreased strength/flexibility/mobility, inflammation and pain. Chronic presentation can be similar with related changes to posture and decreased neuromuscular activity (10). This occurs because the body attempts to protect the injury by recruiting other structures to facilitate the function that the injured component would otherwise complete.

A Practical Approach To Chest Pain

Keep in mind that this framework is NOT intended to suggest a perfect method to treat each condition. We will explore a general treatment framework that you can expect when seeking treatment for chest pain. Within this framework adjustments are made case by case to tailor the treatment to the individual. No one treatment is the same.

- Upon arrival it is critical to rule out the possibility of heart disease and underlying condition involvement. This is determined by evaluating history, visual evaluation and asking questions during the standard interview process. Blood pressure may be taken. Imaging and clearance by your physician may be requested before proceeding with treatment (3).

- Examination:

- Observations of posture, gait and breathing (especially laboured breathing patterns).

- Evaluation of all passive, active, and resisted movements that are relevant to the condition. Palpation to feel the quality of the soft tissue is done and is an especially useful tool when done with motion.

- Testing to evaluate pain patterns, assess specific structures and rule in/out specific conditions (3).

- Following examination, treatment will begin. Throughout treatment, breath considerations should be made.

- Hydrotherapy such as heat can be used at this stage. Relaxation techniques are effective means to reduce pain intensity and reduce overall muscle tension at the beginning of every session (4).

- Advanced techniques are then used to treat deeper and reduce trigger points. At this stage, pain associated with nerve compression, joint restrictions, and muscle tension can be relieved (2, 4, 5).

- Zeroing in on pattern-related pain by considering how pain is manifested by specific movements or structural relationships is the next step. You will be guided through precise procedures to address your specific presentation. This is often the final and most critical step in breaking cycles of dysfunction and resolving chronic pain (2, 4).

- Finally, provided to you is a home care protocol to help encourage the progress made during that session. A strong protocol should reflect the progress and changes that occur each session. This can include strengthening, stretching, self-release exercises, hydrotherapy, and activity level considerations.

Wrapping Up

The best intervention for body optimization relies on evidence-based multi-disciplinary strategies (6). This means working together with all health care practitioners to create a stronger community to serve the public. But not only that! Constantly staying updated with the best quality research and having a diverse repertoire of techniques and treatment methodologies. This is how you can rest assured that you are receiving the best care possible. If you think you have chest pain, don’t wait, come see me today for your musculoskeletal needs.

References

- Tania Winzenberg, Graeme Jones, Michele Callisaya. August 2015. Musculoskeletal chest wall pain. Australian Family Physician 44;8:540-544

- Jeanne Massingill, Cora Jorgenson, Jaqueline Dolata, Ashwini R. Sehgal. August 2018. Myofascial massage for chronic pain and decreased upper extremity mobility after breast cancer surgery. Int J Ther Massage Bodywork 11;3:4-9

- Anne M. Proulx, Teresa W. Zryd. September 2009. Costochondritis: Diagnosis and Treatment. 80;6:617-620

- Laura A Frey Law, Kathleen Sluka. August 2008. Massage reduces pain perception and hyperalgesia in experimental exercise pain: a randomized, controlled study. The Journal of Pain 8;9:714-721

- Susanne M. Cutshall, Laura J. Wentworth, Deborah Engen, Thoralf M. Sundt, Ryan F. Kelly, Brent A Bauer. Effects of massage therapy on pain, anxiety and tension in cardiac surgical patients: A pilot study

- Liza Dion, Nancy Rodgers, Susanne M. Cutshall, Mary Ellen Cordes, Brent Bauer, Stephen D. Cassivi, Stephen Cha. June 2011. Effects of massage on pain management for thoracic surgery patients. Int J Ther Massage Bodywork 4;2:2-6

- John A. Ambrose, George Dangas. May 1999. Unstable angina current concepts of pathophysiology and treatment. Arch Intern Med 160;1:25-37

- Steven D. Waldman. (2003). Atlas of Uncommon Pain Syndromes. Retrieved from http://www.pocayo.com

- François Verdon, Bernard Burnand, Lilli Herzig, Michel Junod, Alain Pécoud, Bernard Favrat. September 2007. Chest wall syndrome among primary care patients: a cohort study. BMC Family Practice 8;51

- Tero AH Järvinen, Markku Järvinen, Hannu Kalimo. February 2014. Regeneration of injured skeletal muscle after the injury. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J 3;4:337-345